Blog search

Blog archive

RSS

Blog

24 September, 2025 Comments (0)

In any passion or hobby, there are aspects we don’t enjoy as much as others; like pin backs! This guide details the different types of pin backs and how to use them.

11 August, 2025 Comments (0)

Among our historic jewelry tool and die collections is Beaucraft, a silver jewelry company established in 1947 and one of many Italian-owned jewelry companies that sprouted and bloomed during the early to middle 20th century in Providence, Rhode Island.

28 May, 2025 Comments (0)

If you're looking to start using inlay in your jewelry-making and metalsmithing, this is the first place you should stop! We talk about the different types of techniques, tools, and resources for beginner and intermediate inlay.

17 February, 2025 Comments (0)

In honor of our March 2025 Mystery Box, we're teaching you all about the French buttons in our collection!

04 February, 2025 Comments (0)

In this extensively researched article, learn about several styles of hair jewelry from hair sticks to beads, the histories behind them, and how to make them using Potter USA tools.

02 October, 2024 Comments (0)

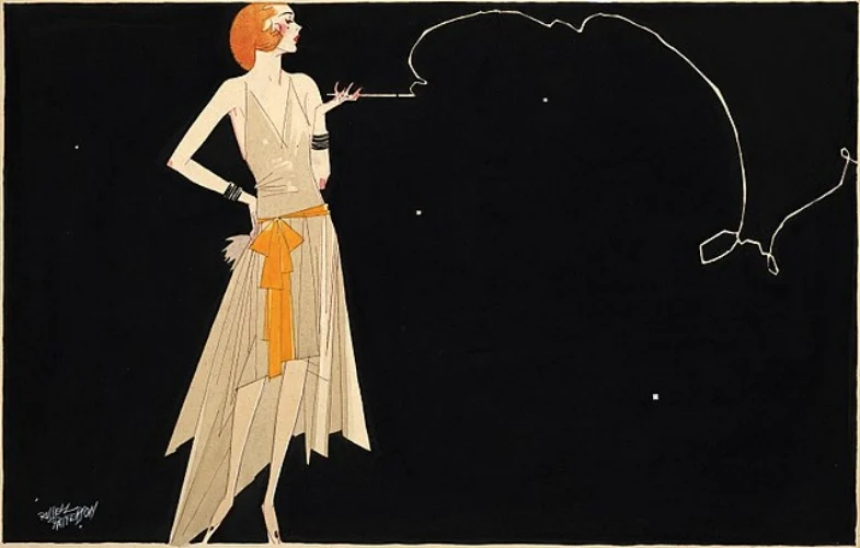

We explore the vibrant history of the cocktail ring and the different styles of cocktail rings in our collections.

18 July, 2024 Comments (0)

Featured in this week’s impression die spotlight are dozens of medallions, coins, and pins, all of which have a rich history that needs to be shared. Continue reading to learn about a few of our favorites!

28 September, 2023 Comments (3)

PotterUSA celebrates the first major tool & die company Kevin Potter ever bought.

21 March, 2021 Comments (2)

Read this blurb about the Cranston Fancy Wire Co., our historic collection of wire rolls from 1867, and how it came to the trusted hands of Vincent Potter in 2018.

21 March, 2021

The story of the Providence Jewelry Museum, which is to say: the story of American jewelry itself. An interview with Peter DiCristifaro offers a broad view of the changes in the jewelry industry.

- 1

- 2

_860.png)